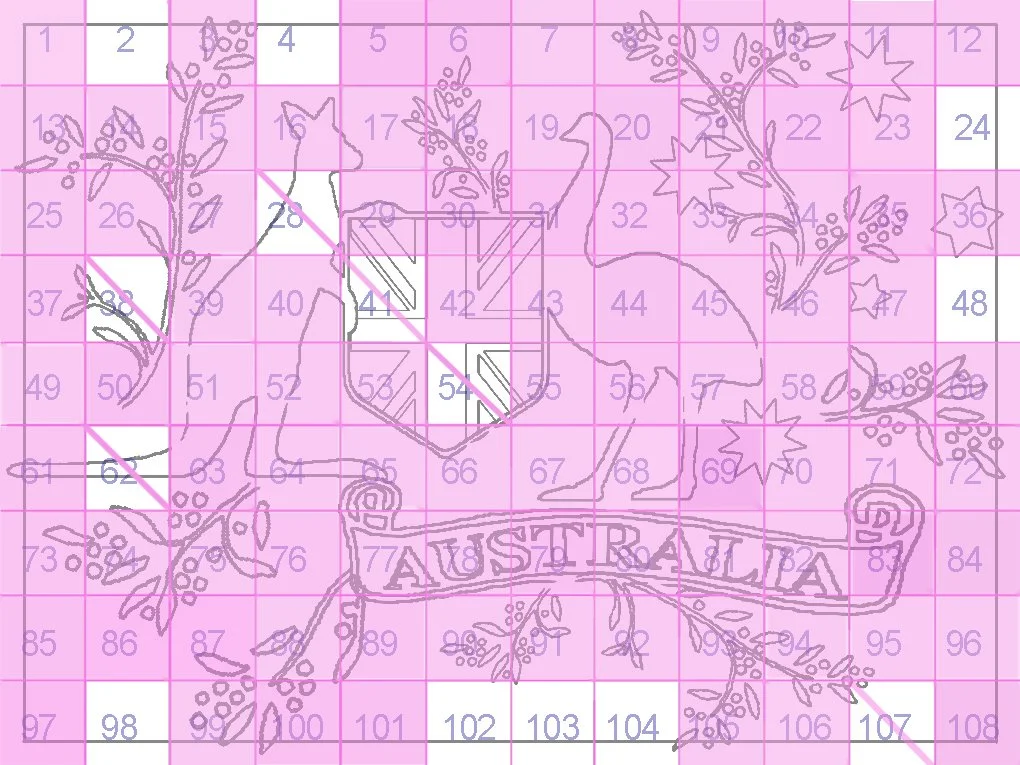

National Life and Landscapes- Australia

The emerging image as at January 26th 2026.

Participation in this project is now closed.

Tiles completed are in pink. Tiles selected, not yet returned have a strike-through.

Progress from the launch at “Groundfloor Conference”, Kandos, March 2024

Image map with 108 “tiles”. Each tile is 10 x 10cm. Overall size 90 x 120cm.

Social Identity in National Life and Landscapes

Palau de la Musica 2012

mixed media on paper

40x40cm

25 participants

Produced at the exhibition “National Life and Landscapes -collaborations” Bar del Convent San Agustin, Barcelona, May 2012 and afterward in London, Singapore and Australia.

Participants were supplied with a numbered paper tile 10x10cm. The tile would be a portion of line drawing of Palau de la Musica, Barcelona. Collaborators were asked to paint or colour their tile in a manner of their choice. When complete, the artist re-composited all the tiles and re-constituted the image.

Social Identity in National Life and Landscapes

The title of the body of collaborative works, comes from the text National life & landscapes: Australian painting, 1900-1940 by Ian Burn (Bay Books, Sydney & London. 1990). Burn proposes that the romantic and classic threads of Australian post-colonial landscape conceptions were not fully resolved by 1940, or even by the time of its publication at the end of the 20th century.

Burn identifies social and cultural conditions in Australia that shape how landscape is viewed as a site of national and social identity. He argues, “…the fictional life of the Australian landscape persists undiminished. It survives, even at the end of the twentieth century, as a key means of validation of both white and black presence in the land”.

In this collaborative project I suggest that social identity is formed and perpetuated as a fiction for communities, nations, and individuals. In the global flux of people across borders, and as the international participants in this project shows, Burn’s Australian thesis is applicable more broadly to nationhood, community, and personhood. But what of personal, subjective experience?

“Difference is no matter of indifference. Yet the politics of modernism has not (had not at the time of writing) been seriously questioned in this country…the antidote is a methodology capable of refining our sensitivity to difference and to multiplicity and diversity within and without the cultures of Australia”

In the Australian context, Burn’s project has been taken up in the cultural sectors with the rise into prominence of contemporary Aboriginal creative practice. Particularly, but not exclusively, by the Central Desert painting communities, where the individual mark is celebrated, and co-opted into accepted traditions and storylines, and often produced with others. These practices help to dismantle the Western Humanist elevation of the individual.

“National Life and Landscapes: Australian Painting 1900-1940”, published in 1990, brings to light the unresolved parallel modes of landscape representation in the Australian modernist era. The accommodation by each of the two camps of pictorial pastoralism and modern formalism had by the 1940’s only partially occurred. Burn asserts that the Second World War interrupted the resolution of this most vibrant discussion. “The landscape tradition was able to appropriate- and transform itself by- many of the approaches and techniques of the modern movement. A more self-conscious process of picture making combined a knowledge of form in art with the accumulated knowledge of the landscape”. By the end of the century this was still about as far as the discussion had progressed. Many vital, exploratory artistic excursions were made in the intervening period 1940-1990, and landscape as a genre still held pre-eminence as the site of national difference and identity.

Art Gallery 2012

50 mixed media parts 19x19x0.3cm mdf

95 x 190cm overall

This collaboration was conducted before and during its exhibition at Salerno Gallery in Sydney, as a slowly revealed image. Paints and brushes were made available to visitors in the gallery.

Vincent 2013

Ink and coloured pencil on paper

40.5 x 34cm

Produced in collaboration with Arts in Health Symposium delegates at Western Plains Cultural Centre, Dubbo. I was invited to deliver a talk on the integration of health in art and sought participation by handing out drawn tiles and coloured pencils during my session. I re-composited the image at the end of the talk on an easel at the podium.

Wattie Creek 2013

Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pours soil into the hand of Gurindji traditional landowner Vincent Lingiari at Wattie Creek, Northern Territory, Australia, 16thAugust 1975. Photograph Mervyn Bishop, courtesy the Australian Government.

oil crayon and ink on paper, collaboration in 400 parts 10x10cm

200 x 200cm overall

Annette Simpson and Jack Randell facilitators. Mervyn Bishop is the original creator of the photograph from which this image is derived. Mervyn was consulted before, during and after the project and the work was produced with his blessing. Mervyn honoured us with an acknowledgement of country when the collaboration was launched at the exhibition “Tracks'“ at Western Plains Cultural Centre, 2013.

Participation in this artwork and exhibition was free, and participation was invited under the Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivatives terms of Creative Commons– http://creativecommons.org.au/learn-more/licences

Wattie Creek is the re-investment in the political and social values contained in this historic image.

“…belonging is a type of emotional gravity. An oscillation between person and place. You belong when you have a place that feels like a person – it has character – and a person feels like a place – they become a space you enter where you can be whatever you want to be with them. That’s how you know you belong. That’s why you can take someone from Afghanistan, but you can never take Afghanistan away from them.”

-Akram Aziri

“A fortunate life: From Afghan refugee to Young Australian of the Year”

Dubbo Weekender Saturday, 03 August 2013 interview with Akram Aziri by Jen Cowley.

Babel 2015-18

mixed media on card

52x60cm

The 17th collaborative work in the series 'National Life and Landscapes'. Unlike previous open call-outs, individuals were invited based on contact with the facilitating artist. The range of collaborators was as socially, rather than geographically as wide as possible. They range from professional to unemployed, politically high profile to incarcerated, well-known artists to the emerging.

This work was researched in part by a visit in December 2015 to the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam http://www.boijmans.nl/en/ where "Tower of Babel" c.1565 by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, was on display.

Babel is an analogue replica of aggregated web systems. Not to thwart the virtual, but to test the validity of interactivity and its emergent aesthetic. The disintegrating verisimilitude of this method of image making, is counterpoint to both the Bruegel system of production (oil on board), and the museum charter of preservation of stasis. The Bruegel original is predicated on its lineage, an arboreal canon that arrives at the glorious status of the work of art most precious to the Boijmans Museum. Our Babel, while not quite a rhizome in the sense that Deleuze and Guattari meant, nevertheless has a subject and signifier ratio of N minus 1; that is, not completely the interconnected matrix, but a web with not all the information available. The multiple authors in this manifestation of Babel, some with connections, some unknown, bring a range of purposes to the interpretation, but only in their segment or “tile”. Each part will be consequential to its whole and neighbours but is unlikely to be influential in the whole of the image. My curatorial precept of complete liberty in the participator’s response generates direction for the work although cannot signify a purposeful outcome. Serendipity rules.

National Life and Landscapes operates at 3 levels: participation, collaboration, and social pluralism. Creating a site where individualism drifts toward tribalism, but never completely coalescing into a group.

Visitors to “Yahyoi Kasuma : The obliteration room” 2017-2018 at Auckland Art Gallery Toi Otamaki or Pipilotti Rist “Sip my Ocean” at Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney over the same summer period, were given the opportunity to contribute to the making of the works. In-gallery active engagement with the artwork, venue and artist promotes the 3 levels: participation, collaboration, and social pluralism.

Yahyoi Kasuma : The obliteration room 2017-2018 at Auckland Art Gallery Toi Otamaki

https://www.didiermary.fr/yayoi-kusama-interactive-obliteration-room/

https://www.aucklandartgallery.com/whats-on/exhibition/yayoi-kusama-the-obliteration-room

The active aesthetics of participation only marginally change the visual or sculptural components of these works. The pedagogical differences between styles of learning might suggest that a sporty, active art punter will receive a better understanding of the artwork in this manner, than say a visual learner reflectively engaged at arm’s length. The discursive gallery goer may better understand the works by considered non-engagement, conceptually delighting in the absent/presence of the artist.

Creative practice of this type is ephemeral, social, transient and is thrilling to audiences for its disruptive premise. Live art in flux- audience at the wheel- artist back of house- ground zero for art. After the lights go down, and the gallery attendants tidy up a bit, and leave the building the work loses some of its potency as a relational aesthetic. Because the dawning is that without the individual- the sum of participants minus one (N-1), the art is still essentially the same. The fictionalised performative gesture of participation, collaborative behaviour and social plurality becomes the greater part of which the work is a part, not a thing unto itself.

This I believe is one of the legacies of First Nations art, at least as viewed through a contemporary lens.

Oh, the River People 2013

digital Projection HD video 1920x1080 pixels 4.30min continuous play

collaboration 108 parts

Jack Randell coordinator, Peter Aland technical advisor

Vimeo- Oh, the River People http://vimeo.com/77194433

A re-image; a photograph of the Waambul (Macquarie River), exposed through an international callout to the apparatus of the internet and social media, developed with the chemicals of creative impulse.

Enlightenment; the validation of personal creative choice made in a spirit of goodwill. A projection both myopic and the multiple co-existing. Herman Hess’ Siddhartha found enlightenment by a river with the realisation that its end, beginning and constantly moving state exists simultaneously in every moment of its flow.

“And when Siddhartha listened attentively to the thousandfold song of the river, when he did not fasten on the suffering or the laughing, when he did not attach his mind to any one voice and become involved in it with his ego -when he listened to all of them, the whole, when he perceived the unity, then the great song of a thousand voices formed one single word: OM, perfection.”

Hess, Hermann “Siddhartha” Translated by Sherab Chodzin Kohn. Shambhala Publications, Boston 2000

In the project “National Life and Landscapes”, which has included a diverse range of over a thousand people both artists and non-artists, is to test the idea of disparate voices addressing a known or unknown outcome.

Each work is neither mythos nor logos, but a social creative space. It is not resolved as a romanticised future, nor a formalised past. It is a working method validating uniquely personal judgements, in a matrix of somewhat indifferent investments in a substantial guided whole.

Review by Maurice O’Riordan. ART MONTHLY Australia Issue 266 Summer 2013/14 p 46

Tracks

Western Plains Cultural Centre, Dubbo, 19 October to 1 December 2013: wpccdubbo.org.au

Coursing its way along the Macquarie and into the cultural heart of Dubbo (NSW), or at least one of them, in the Western Plains Cultural Centre, is the exhibition Tracks by Dubbo-based artists Annette Simpson and Jack Randell. Both have sustained individual practices over numerous decades; Randell initially as a painter at a time when boundaries between painting and sculpture had well collapsed, and Annette primarily as a printmaker. Both have had their share of metropolitan life; Annette still with one foot in Sydney, maintaining a studio and teaching position there.

Collaboration is a richly embedded concept in Tracks; both artists have collaborated on a series of mixed-media paintings, each handing the work over to the other to continue working on at varying stages; and the exhibition includes four large-scale collaborative works which the artists have set in motion and which involve hundreds of participants from near and far, both before and during the works’ gallery exhibition. Wattie Creek is one such work, a two-by-two-metre grid comprising 400 squares which are filled by the crayon colourings of individual participants. Each square given to participants already has some black line-work which forms an overall pattern to suggest the work’s source image: Mervyn Bishop’s iconic photograph of PM Gough Whitlam pouring soil into the hands of Gurindji elder Vincent Lingiari, at Wattie Creek (NT), 16 August 1975. Bishop, who’d spent some of his early schooling in Dubbo, was a guest speaker at the exhibition’s official opening early November. A framed print of his colour photograph hangs beside the sprawling Wattie Creek mosaic-grid which takes up the gallery’s central wall.

On an adjacent wall is another mosaic-grid-based work, Read Between the Lines, comprising 120 sheets of paper, each bearing an etched line by Simpson (its overall outline softening the grid), and each worked on by 120 different participants: from well-established artists to the totally amateur – free to create anything on the sheet provided without a specific thematic or visual anchor. It makes an interesting foil to Wattie Creek with its more politicised frame of reference, even as this work’s evolving image clearly takes on its own aesthetic life. Both works, in fact, suggest an aesthetic of democracy – as act and ideal.

The grid-form and its sense of pixilation is fulfilled in the collaborative (108-part) video-mosaic work, Oh, the river people, screening on the gallery’s back wall, an audiovisual ode to Dubbo’s Macquarie River, or Wambool as known in the local Wiradjuri language. Beside its dream-like flickering hangs a number of Randell’s Black Snake mixed media paintings. Yes, the exhibition still has a home for the individual hand including Simpson’s Me ‘n Mum ‘n Nan ‘n Special Nan collagraph print, a striking genealogy-by-knickers. And a home too for the stone bush-curlew, a critically endangered species in the state, whose plight informs the other collaborative work in Tracks, an interactive piece involving a stamp modelled on the curlew’s footprint. At opposite ends of the gallery Bush Stone-Curlew and Oh, the river people fittingly frame the exhibition’s democratic bent in terms of an ecology.

The video work Oh, the River People is viewable at: http://vimeo.com/77194433